Sydney—22 February 1970—began like any other summer Sunday at the airport: hot tarmac, turbine breath, and the long procession of departures. Fourteen-year-old Keith Sapsford had run away again, this time from Boys’ Town in Engadine, the Catholic home meant to steady his compass. He wanted motion, not rules. He wanted out.

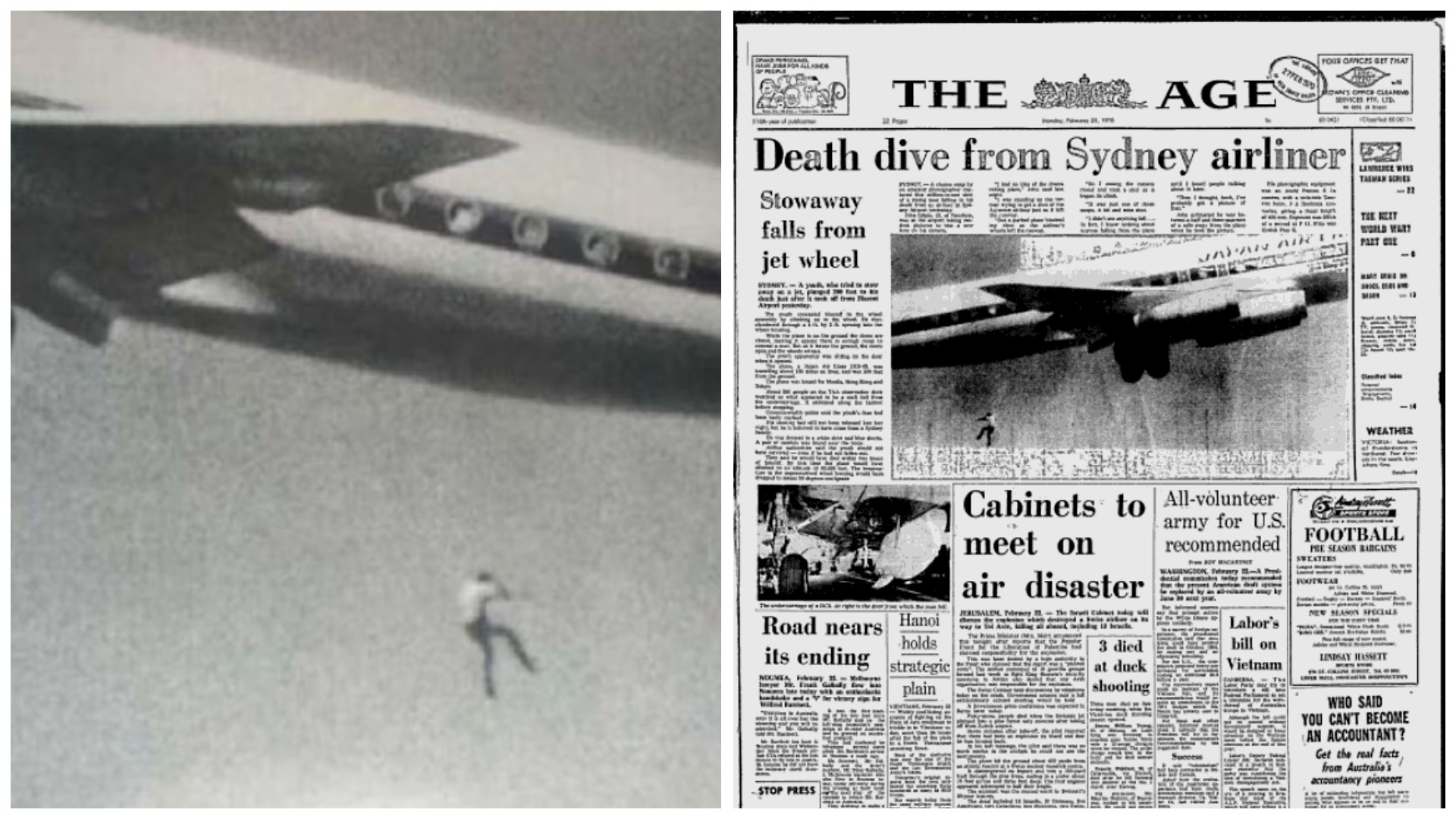

The airport perimeter was looser in those years—fewer cameras, more gaps—and Keith found one. He slipped through to the stands, where aircraft squatted like silver whales between tides of flights. A Japan Air Lines DC-8-62, registration JA8031, stood ready—Flight 772 bound for Manila, then Tokyo—its skin shimmering with heat. Keith climbed into the dark rectangle of the landing-gear bay, a space meant for steel and hydraulics, not a boy with a world-sized ache. He crouched on the inner door, close to the strut, close enough to be hidden if anyone shone a weak light and hurried on. Minutes stretched. Baggage thumped. Checklists droned. At 12:51 p.m., the DC-8 began its takeoff roll along Runway 34. The cockpit crew called speeds; the aircraft rose. In those first seconds after liftoff, the landing gear starts to tuck away. The bay you think is a cave becomes a machine. Doors open. Wheels pivot. The geometry changes. Keith was still there—no seatbelt, no rail, only metal and air. About one minute after liftoff, at roughly 200 feet above the field, someone on the ground saw a shape fall from the left main gear. It was a boy in a short-sleeved shirt and shorts, dropping through sunlight he had mistaken for safety. Across the field, an amateur named John Gilpin stood behind a camera, just testing a new lens. He tracked the climbing jet and clicked in reflex, unknowing. When he later developed the film, he would find the most harrowing silhouette in Australian aviation lore: a 14-year-old suspended midair, feet first, hands upturned toward a sky that would not hold him.

The Japanese jet continued north, eventually diverting to Darwin; inspectors there would find fresh handprints and shoe marks in the left main gear compartment. The airplane itself was unharmed; it was never meant to carry a passenger there. On the runway at Sydney, first responders found the body. The name followed. The city tried to understand. Keith’s father, Charles Sapsford, a university lecturer, would later tell reporters that his son only wanted to “see the world.” He had warned him, he said, about another boy who died in a wheel-well overseas. Wanderlust doesn’t bargain. A week after the fall, in a darkroom, the image bloomed: the boy and the jet in the same terrible frame, a pinprick of human hope dwarfed by machinery and sky. LIFE magazine would run the picture in its March 6, 1970 issue under “Parting Shots,” and the photo would circle the globe—the last portrait of a dream in freefall.

The official report from what is now the Australian Transport Safety Bureau fixed the sequence with forensic calm: unattended hours, an accessible bay, a takeoff, a fall. It named the aircraft, the time, the altitude, and the prints on metal. It did not—could not—measure longing. Could he have survived if he hadn’t fallen? Almost certainly not. Wheel-wells are brutal places—thin air, savage cold, and unforgiving mechanics. At cruise, oxygen thins to a fraction; temperature can plummet far below freezing. Even the rare survivors often arrive unconscious, hypothermic, or worse. FAA/CAMI researchers have logged a ~75% fatality rate across decades. Pilots’ walk-around checks use flashlights and trained eyes, but they can’t probe every dark recess; the bay extends beyond easy sightlines. On that day in 1970, the inspections were by the book—and a boy still found a blind corner.

Keith’s story keeps resurfacing because it compresses so many contradictions: adventure and naiveté, openness and risk, a global age beginning and the smallness of a single body against it. He wanted out, and the world he wanted was on the other side of a locked door. He chose the only door that opened for him that day, and it opened the wrong way. The photo is difficult to look at, precisely because it is so clean—no blur, no gore, just the stark geometry of a moment too late to undo. In the years after, the picture became a permanent warning in newspapers and classrooms: not a dare, but a deterrent. Security tightened; fences rose; protocols hardened. Even so, desperate people would try again elsewhere, and most would die for it. The sky can be merciless to those who cling to its edges. The father’s words—“he only wanted to see the world”—read like an epitaph for both a son and an era. If there is a gentler ending to be found, it is in what the image did: it stopped others. It made the danger undeniable, immediate, unforgettable. And if there is an unexpectedly human twist, it is this: two strangers—one boy, one photographer—collided in history for less than a second, and together they created a message the world could not ignore. In that way, Keith finally did what he wanted: he crossed borders. He reached Tokyo, London, New York—not in a cabin, but in a cautionary frame that traveled farther than any ticket could have taken him. The lens clicked. The city gasped. The world learned. And a boy who longed to see the world made sure the world would always see him.

Sources

-

Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB), Accident Investigation Report: DC-8-62 JA8031, Sydney (Kingsford Smith) Airport, 22 Feb 1970 (details on flight number, timeline, altitude, left main gear bay, physical traces).

-

The Age (Melbourne), 23 Feb 1970, front page (“Death dive from Sydney airliner”)—contemporary coverage confirming identity/age and event timing. (Google News)

-

NZ Herald / news.com.au (feature recap; runaway from Boys’ Town; father’s prior warning; photographer realizing image a week later). (NZ Herald)

-

LIFE Magazine, week of Mar 6, 1970, “Parting Shots” (publication of John Gilpin’s image). (Google books)

-

FAA Civil Aeromedical Institute (CAMI), Survival at High Altitudes: Wheel-Well Passengers (risk of hypoxia/hypothermia; rarity of survival). (libraryonline.erau.edu, faa.gov)

-

All That’s Interesting (compiled background; clothing, 200-ft fall phrasing; cites NZ Herald/Yahoo). (All That's Interesting)